March 24 is World TB day.

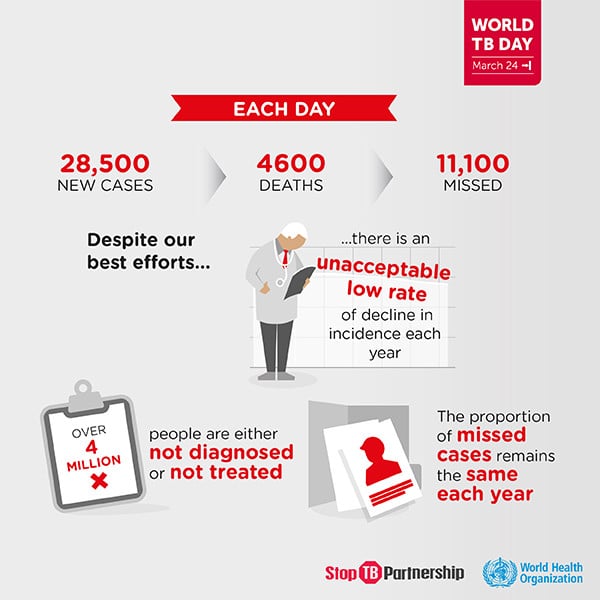

This annual event commemorates the date in 1882 when Dr. Robert Koch announced his discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the tuberculosis-causing bacteria, and it aims to raise global awareness of this devastating disease. World TB day, proposed at the 100th anniversary of Koch’s discovery 1882, was introduced in 1996 to celebrate the successes of anti-TB therapy and “DOTS” (Directly Observed Treatment Short course), the internally recognized strategy to control TB that combines sustained political and financial commitment, diagnosis, short-course anti-TB treatment, drug supply, and standardized recording and reporting. In 1996, however, the appearance of multidrug-resistant TB and a deadly association of HIV and TB already predicted that the fight against TB would be long and arduous. Today, despite significant global efforts and scientific progress, TB remains the deadliest infectious disease worldwide with about 10.4 million new cases and 1.7 deaths in 2016 alone – or 4,500 lives lost every day.

World TB day 2018 is themed “Wanted: Leaders for a TB-free world”. A TB leader, according to the Stop TB Partnership, is a head of state, minister, mayor, governor, parliamentarian and community leader.

Politicians are mentioned deliberately here. Government stewardship is a highlighted principle in the global “End TB strategy”. In November 2017, global health ministers assembled in Moscow and agreed to the “Moscow Declaration to End TB”. And in 2018, the first UN General Assembly High Level Meeting on TB will follow aiming to place TB as a global political priority. Political leaders need to keep their word and commit to universal health coverage, sustainable financing and research & development of new tools, and they need to remain accountable throughout the progress of ending TB. The World TB day theme serves as a gentle reminder of these obligations.

A TB leader, however, is also every person active in TB response – civil society advocates, health workers, doctors or nurses, NGOs and all other partners and personnel involved in the fight against TB.

At APOPO, in our 20-year history and one-and-half decades of TB research, we have encountered many of these formidable TB leaders, who have contributed to the cause through ideas, vision, hands-on support, collaboration and financial assistance to embark on something new: to train rats to detect TB.

APOPO’s operational headquarters and first TB research sites began in 2002 in Tanzania, on the grounds, and supported by the Sokoine University of Agriculture. Research in Mozambique (since 2013) and Ethiopia (2018) has followed. These three countries have a common cause in that they face a high TB burden, and approximately half of their nationwide TB patients remain undetected. These ‘missed’ TB positive patients often include the most vulnerable and those without proper access to care. Left untreated, TB patients can pass on the pathogen to others, and up to two thirds of TB patients will eventually die.

APOPO is conducting ongoing research into developing and deploying TB detection rats as a diagnostic tool. In brief, human sputum samples are collected from partner DOTS clinics that have already tested them for TB using locally available sputum smear microscopy, which has a limited sensitivity. Rats re-test these (heat-inactivated) samples and make additional positive indications that are then rechecked using WHO endorsed confirmation tests such as LED fluorescence microscopy. Confirmed TB-positive results are conveyed to clinics which orchestrate patient treatment. This research approach raises our partner clinic detection rates by 40%.

The action does not end here. We are engaging in partnerships with community health workers – often former TB patients who have decided to join patient organizations and take a lead – guiding newly diagnosed TB patients and linking them to care. The sample evaluation by rats also feeds into basic research on scent detection and on biomarkers, i.e., what the rats actually smell. The research on the rats may lead and guide the development and refinement of synthetic diagnostic devices, such as e-noses.

That this innovation roots in Tanzania is not by coincidence. The United Republic of Tanzania is a TB leader itself. It is in Tanzania, where the first national nationwide tuberculosis program was founded, the NTLP (Tanzanian National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Programme). And it was here, where the shorter supervised anti-TB treatment has been trialed in the hope of achieving higher cure rates. Tanzania’s research and experience would later feed into the new control strategy of the WHO: DOTS.

Last but not least: we all can be TB leaders through our efforts to end TB in our own work or terrain. This can be as easy as spreading the word that TB still exists, kills, and is a major issue in economically challenged countries. As Lucica Ditiu, the Executive Director of Stop TB Partnership states : “We owe [it] to us and future generations […]. We must end TB!”

APOPO thanks the health authorities across the countries in which it works for their continued support, as well as our funding partners.